The piece below is republished from Mercian Geologist, volume 19, part 3, October 2018, pp 128–129, with the permission of the author. It gives some excellent detail on the geological references in Song 26.

The library of the British Geological Survey (BGS) has been in existence since at least 1842, the year in which the Survey’s first Director, Henry Thomas De la Beche, first recorded the purchase of ‘books for the Library of the Museum’. The Library today holds many rare old volumes pertaining to geology, mineralogy and fossils, mining, agriculture and topography. In this last category falls a curious work by the poet Michael Drayton (1563–1631), entitled: Poly-Olbion, or, a chorographicall description of tracts, rivers, mountaines, forests, and other parts of this renowned Isle of Great Britaine, with intermixture of the most remarquable stories, antiquities, wonders, rarityes, pleasures, and commodities of the same: digested in a poem.

Poly-Olbion was published in two parts. The first part appeared in 1612, though evidently without a date; it was reissued bearing a date of 1613. A second part was published in 1622, together with the first part, now furnished with a new title-page. BGS holds the 1613 edition of the first part, bound together with the second part, and the book was acquired by the Library on 12 May 1846.

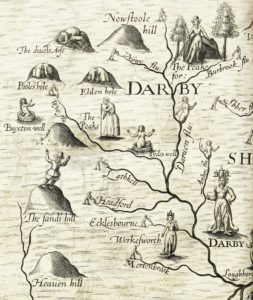

The work is an expansive poetic journey through the landscape, history, traditions and customs of early modern England and Wales. Drayton’s 15,000-line poem, which navigates the nation by way of its principal rivers, is embellished by William Hole’s thirty whimsical engraved maps. The map extract reproduced here accompanies the ‘sixe and twentieth Song’, which occurs in part two (1622), and concerns itself in part with the Peak District of Derbyshire within the drainage area of the River Derwent (here variously called Daruen or Darwin) and its tributaries. Drayton expounds at unusual length on the wonders of the Derbyshire Peak, which must have impressed him greatly.

Here is what he says of the Peak’s mineral products:

For shee a Chimist was, and Natures secrets knew,

And from amongst the Lead, she Antimony drew,

And Christall there congeal’d, (by her enstyled Flowers)

And in all Medcins knew their most effectuall powers.

The spirits that haunt the Mynes, she could command and tame,

And bind them as she list in Saturns dreadfull name:

Shee Mil-stones from the Quarrs, with sharpned picks could get,

And dainty Whetstones make, the dull-edgd tooles to whet.

Wherefore the Peake as proud of her laborious toyle,

As others of their Corne, or goodnesse of their Soyle,

Thinking the time was long, till shee her tale had told,

Her Wonders one by one, thus plainly doth unfold.

The reference to the extraction of antimony in association with lead is of especial interest. Ford et al. (1993, p. 25) notes that the presence of antimoniated lead ore at Gregory Mine, Ashover has been reported in several 19th century publications, but regards the presence of (workable) antimony in the Derbyshire Peak as unconfirmed by modern work. Our poet however clearly indicates that antimony was being extracted for its medicinal use, along with fluorspar (the ‘Flowers’ in line three). Antimony salts were used in medicine as an emetic and ‘in some eruptive or exanthematous fevers, in catarrhal affections, and as an ointment to be applied externally’ (Wang 1919, pp. 168–9). Trevor Ford has drawn attention to a reference from 1799 to the application of powdered ‘blue fluorspar’ in the treatment of gall stones (Ford 2005, p. 100).

Our poet then follows with an account of the several Wonders of the Peak: the Divels Arse (Devil’s Arse, or Peak Cavern, Castleton), Pooles hole (Poole’s Cavern, Buxton), and Elden hole (Eldon Hole, Peak Forest). From the details given it seems clear that Drayton had entered or at least visited these caves himself.

Concerning Poole’s Cavern:

Whose entrance though deprest below a mountaine steepe,

Besides so very strait, that who will see’t, must creepe

Into the mouth thereof, yet being once got in,

A rude and ample Roofe doth instantly begin

To raise it selfe aloft, and who so doth intend

The length thereof to see, still going must ascend

On mightie slippery stones, as by a winding stayre,

Which of a kind of base darke Alablaster are,

Of strange and sundry formes, both in the Roofe and Floore,

As Nature show’d in thee, what ne’r was seene before.

But Eldon Hole is his favourite:

For Elden thou my third, a Wonder I preferre

Before the other two, which perpendicular

Dive’st downe into the ground, as if an entrance were

Through earth to lead to hell, ye well might judge it here,

Whose depth is so immense, and wondrously profound,

As that long line which serves the deepest Sea to sound,

Her bottome never wrought, as though the vast descent,

Through this Terrestriall Globe directly poynting went

Our Antipods to see, and with her gloomy eyes,

To glote upon those Starres, to us that never rise;

That downe into this hole if that a stone yee throw,

An acres length from thence, (some say that) yee may goe,

And commanding backe thereto, with a still listning eare,

May heare a sound as though that stone yet falling were.

Ford (2008) tells us that Eldon Hole is the only natural open pothole in the Peak District, describing it as a gash 34 m long by 6 m wide on the southern slopes of Eldon Hill. It descends vertically to about 60 m (200 feet) from the surface, with a low passage off to a large cavern and a further drop to a final depth of 80 m ― so not quite all the way to the Antipodes!

The virtues of the spa waters at Buxton and Tydeswell are described in turn. Then ‘for change’, our poet goes on to describe a curious sandy hill:

A little Hill I have, a wonder yet more strange,

Which though it be of light, and almost dusty sand,

Unaltered with the wind, yet firmly doth it stand;

And running from the top, although it never cease,

Yet doth the foot thereof, no whit at all increase.

Nor is it at the top, the lower, or the lesse,

As Nature had ordain’d, that so its own excesse,

Should by some secret way within it selfe ascend,

To feed the falling backe; with this yet do not end

The wonders of the Peake…

Referring to William Hole’s map we may perhaps see the poet himself ‘running from the top’ of The Sandi hill with what appears to be gleeful abandon. This windswept hill, which no amount of erosion seems able to reduce in height, can in all probability be identified with a hill that occurs in the narrow angle between the converging rivers of Churnet and Dove, immediately north of Rocester and just within the county of Staffordshire. Though unnamed on the 1:25 000 scale Ordnance Survey map, it evidently goes under the name of Barrow Hill, the top of which is marked by a knoll at 150 m above OD to the north of Barrowhill Hall. Geologically this hill is made up of an isolated patch of glacial till resting on Mercia Mudstone and capped by glacial sand and gravel.

View towards Barrow Hill from the River Churnet; the knoll of ‘Sandy hill’ described by Drayton lies just beyond the trees, though in Drayton’s day the whole area may have been unwooded sheep pasture (photo: © D G Bate, June 2018)

It has not been possible with certainty to identify Heaven hill, depicted on the map to the immediate south of The Sandi hill, though it must be part of the hill-range running south-ward from Rocester along the east side of the River Dove, for there is a Havenhouse Farm on this range. Drayton merely refers to the hill in passing when he salutes the Peake hills that run from Nowstoll in the north (Nowstoole hill on the map, which cannot be identified, unless it is an alternative name for Win Hill, lying between the rivers Noe and Derwent) to Heaven hill in the south.

The full text of the Poly-Olbion is accessible online via Exeter University’s Poly-Olbion Project (from which the present writer has derived some of his introductory material): http://poly-olbion.exeter.ac.uk/the-text/

Thanks are accorded to thank Anne Dixon, Chief Librarian at the British Geological Survey, for allowing the writer to photograph the William Hole map.

References

Ford, T. D. 2005. Derbyshire Blue John. 2nd ed. Ashbourne: Ashbourne Editions, 112 pp.

Ford, T. D. 2008. Castleton caves. Ashbourne: Landmark Publishing, 96 pp.

Ford, T. D., Sarjeant, W. A. S. & Smith, M. E. 1993. The minerals of the Peak District of Derbyshire. Bulletin of the Peak District Mines Historical Society, 12 (1), 16–55.

Wang, C. Y. 1919. Antimony: its history, chemistry, mineralogy, geology, metallurgy, uses, preparations, analysis, production, and valuation. 2nd ed. London: Charles Griffin & Co, 217 pp.

David G. Bate

British Geological Survey, Keyworth