One of the recurring soundbites that has populated post-Brexit political discussion is the suggestion that in Britain, we should “have our cake and eat it”. Aside from the strictly practical implications of the phrase – regarding market access and border controls – “having our cake and eating it” describes a complex attitude to Europe that has become culturally ingrained over time. Many people recognise that European immigrants play vital roles in society, whilst simultaneously clinging to the idea of Britain as a plucky, isolated island that repels hostile European invaders.

the strictly practical implications of the phrase – regarding market access and border controls – “having our cake and eating it” describes a complex attitude to Europe that has become culturally ingrained over time. Many people recognise that European immigrants play vital roles in society, whilst simultaneously clinging to the idea of Britain as a plucky, isolated island that repels hostile European invaders.

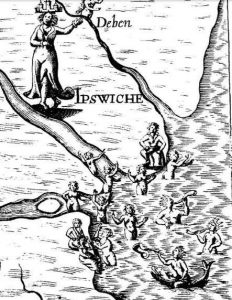

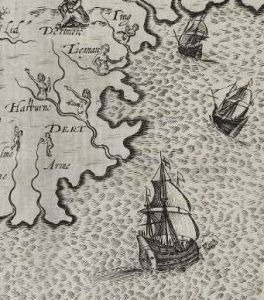

A similar form of cognitive dissonance governs Drayton’s approach to Europe in Poly-Olbion. In the opening address to his Welsh readers, Drayton explicitly identifies the Channel Islands, Jersey and Guernsey, as “our French Islands”. The tone here may be proprietary, in that Drayton is drawing attention to the fact that Britain has prevented these Norman territories from being retaken by France, but equally, Drayton allows the islands to retain their “French” character. From the outset, Drayton presents a Britain that is culturally diverse, if slightly combative, in its relations with Europe.

Two passages further indicate that Drayton may wish Britain to have its cake and eat it. On the one hand, there is Drayton’s patriotic description of Kent, sung in the voice of the river Stour:

O noble Kent, quoth he, this praise doth thee belong,

The hardest to be controlled, most impatient of wrong.

Who, when the Norman first with pride and horror swayed,

Threw off the servile yoke upon the English laid;

And with a high resolve, most bravely didst restore

That liberty so long enjoyed by thee before.

Not suffering foreign Lawes should thy free Customs bind,

Then only showd’st thy self of the ancient Saxon kind.

Of all the English Shires be thou surnamed the Free,

And foremost ever placed, when they shall reckoned be. (Song 18, ll.729-38)

The language here is strongly nationalistic, and would be considered old-fashioned were it not for the resurgence of such sentiments among far-right groups throughout Europe. The personality Drayton bestows upon the Stour is committed to an independent, hermetically sealed Britain, where the more established Saxons throw off the “servile yoke” imposed upon them by Norman invaders. The emphasis upon not being “controlled” by a threatening “foreign” other, and upon the county’s inhabitants bravely restoring their freedom is indicative of the hostile dialectic often used to construct Britain’s identity in opposition to Europe. The praise heaped upon Kent for “Not suffering foreign Lawes should thy free Customs bind” feels particularly contemporary, bringing to mind the rhetoric used by those who argue against Britain being subjected to EU regulation.

Drayton demonstrates a very different attitude to Britain’s national identity when commenting on the role of migrant labourers in Norwich. At the time, Norwich was the fourth largest city in the country, and its population was bolstered by the arrival of Protestants from France and the Low Countries, who had fled Catholic persecution. The city is described as

That hospitable place to the Industrious Dutch,

Whose skill in making Stuffs, and workmanship is such,

(For refuge hither come) as they our aid deserve,

By labour sore that live, whilst oft the English starve;

On Roots, and Pulse that feed, on Beef and Mutton spare,

So frugally they live, not gluttons as we are. (Song 20, ll.35-40)

This passage is striking in that Drayton not only describes the economic value of “Industrious” Dutch immigrants, but asserts that their productivity makes them deserving of “refuge”. The Dutch are not just tolerated because of their skill in manufacturing textiles, but are actively welcomed, and even compared favourably to the English. The suggestion that they contribute to the city whilst surviving on spare meat and foraged vegetation, unlike the English “gluttons”, deflects the familiar accusation that immigrants place a strain upon local infrastructure. Here,  integration with Europe brings only cultural enrichment and economic prosperity.

integration with Europe brings only cultural enrichment and economic prosperity.

Admittedly, these sections are not equivalent. One describes an historical invasion, whilst the other comments on an immigrant community that was growing as the poem was written. But when read together, they do show that, for Drayton, conflicting narratives about Britain’s relationship with Europe can easily co-exist. Sometimes, Britain is the island fortress that has “checkt Iberias pride” (Song 1, l.232), but in other parts of the poem, it is a home for incoming refugees, along with numerous generations of migrants from the Trojans, to the Romans, to the Angles. The sense that Britain is an independent entity, ideologically separated from the rest of Europe co-exists with the acknowledgement that immigration from the mainland has been vital in shaping Britain’s character. For Drayton, as for many of today’s politicians, there is value in propagating both narratives simultaneously. Unfortunately, only in poetry is it possible to have one’s cake and eat it.

Fraser Buchanan, University of Oxford