Drayton’s representation of Somerset in Song 3 of Poly-Olbion takes us back to a time when water was an accepted part of the regional environment. Schemes to drain the Somerset Levels did not begin in earnest until later in the seventeenth century. While we know that locals in Drayton’s time pursued more rudimentary ways of managing water, Poly-Olbion is notable for its appreciation of this watery landscape as not only richly fertile but also beautiful. The poem acknowledges no alternative to traditional ways of managing this land, for the simple reason that no alternatives had yet been proposed. Yet it makes very clear, and serves as an interesting historical reminder, that sodden land is not necessarily useless land.

Somerset, as William Hole’s map also demonstrates, is a land dominated by water. The village of Muchelney, a key site of flooding in 2014, was then ‘the Isle of Muchelney’. Similarly, Glastonbury, surrounded as it was by rivers and ‘Marshie grounds’, was known as ‘the Isle of Avalon’, the rivers surrounding it lending weight to a contemporary desire to locate Arthurian legend in the English countryside. Drayton was only too pleased to endorse this mythology. Now, while it is still possible to stay at the Isle of Avalon Caravan Park, inundating waters are seen as aberrant, and there is little reminder of what made the Arthurian identification plausible for the early modern mind.

Somerset, as William Hole’s map also demonstrates, is a land dominated by water. The village of Muchelney, a key site of flooding in 2014, was then ‘the Isle of Muchelney’. Similarly, Glastonbury, surrounded as it was by rivers and ‘Marshie grounds’, was known as ‘the Isle of Avalon’, the rivers surrounding it lending weight to a contemporary desire to locate Arthurian legend in the English countryside. Drayton was only too pleased to endorse this mythology. Now, while it is still possible to stay at the Isle of Avalon Caravan Park, inundating waters are seen as aberrant, and there is little reminder of what made the Arthurian identification plausible for the early modern mind.

Drayton’s emphasis on fertility is perhaps more arresting. In his poem, the manifold rivers of this landscape are not only beautiful in themselves; they underpin a richly productive rural economy. The River Bry is thus beset by ‘many a plump-thigh’d moore, & ful-flanck’t marsh’. Wiltshire, by contrast, is represented as wasted, its land overly devoted to hunting and other gentlemanly exercises. But Somerset ‘her selfe to profit doth apply, / As given all to gaine, and thriving huswifrie’:

This liketh moorie plots, delights in sedgie Bowres,

The grassy garlands loves, and oft attyr’d with flowres

Of ranke and mellow gleabe; a sward as soft as wooll,

With her complexion strong, a belly plumpe and full.

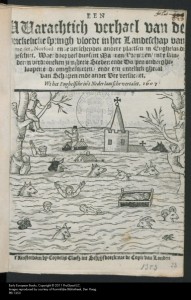

There are many criticisms, from a practical point of view, that one might make of Drayton’s depiction of the Levels. In particular, these passages lack the rich detail of regional farming practices that he devotes to the fens in East Anglia (see esp. Song 25), nor do they acknowledge calamitous floods such as those of 1607, an event so disturbing that it attracted attention as far afield as the Netherlands. There is perhaps, as many Somerset residents might complain today, more than a touch of metropolitan fantasy to the whole thing. Yet Song 3 remains striking nonetheless as a representation of a landscape which has not yet learned, as Drayton sees things, that water needs to be tamed, and that marshes need to be drained. And he presents it as a place both of abundance and beauty.

There are many criticisms, from a practical point of view, that one might make of Drayton’s depiction of the Levels. In particular, these passages lack the rich detail of regional farming practices that he devotes to the fens in East Anglia (see esp. Song 25), nor do they acknowledge calamitous floods such as those of 1607, an event so disturbing that it attracted attention as far afield as the Netherlands. There is perhaps, as many Somerset residents might complain today, more than a touch of metropolitan fantasy to the whole thing. Yet Song 3 remains striking nonetheless as a representation of a landscape which has not yet learned, as Drayton sees things, that water needs to be tamed, and that marshes need to be drained. And he presents it as a place both of abundance and beauty.

Andrew McRae