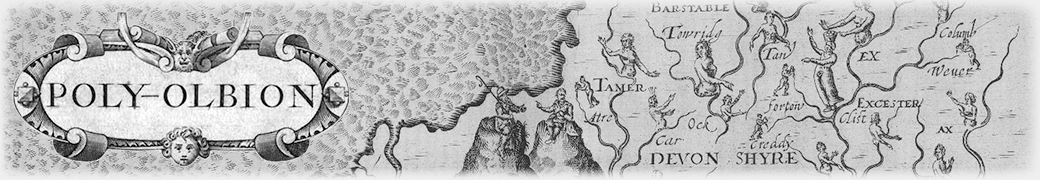

Drayton’s concern for the felling of trees in Britain is one of the most striking aspects of Poly-Olbion. For Drayton, deforestation was not only a waste of national resources but a threat to the beauty and spirit of the nation. Whether Drayton’s perspective can be described as “green” in the modern sense remains a matter for debate, but passages like the lament for Andredsweald provide a vital point of connection between modern readers and a poet writing four centuries ago. The old forest known as Andredsweald, covering a large part of the southeastern English counties of Kent, Sussex, and Surrey, was decimated from the sixteenth century onward as trees were felled to provide timber for ships and charcoal for the iron industry. Today, part of this region is included within the High Weald Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty, and a walking route invites visitors to explore some remnant of the ancient forest.

| To seaward, from the seat where first our song begun, Exhaled to the south by the ascending sun, Four stately wood nymphs stand on the Sussexian ground, |

|

| Great Andredsweld’s sometime: who, when she did abound, In circuit and in growth, all other quite suppressed: But in her wane of pride, as she in strength decreased, Her nymphs assumed them names, each one to her delight. As, Water-down, so called of her depressed site: And Ash-Down, of those Trees that most in her do growe, Set higher to the downs, as th’other standeth low. Saint Leonards, of the seat by which she next is placed, And Whord that with the like delighteth to be graced. These forests as I say, the daughters of the Weald (That in their heavy breasts, had long their griefs concealed) Foreseeing, their decay each hour so fast came on, Under the axe’s stroke, fetched many a grievous groan, When as the anvil’s weight, and hammer’s dreadful sound, Even rent the hollow woods, and shook the queachy ground. So that the trembling nymphs, oppressed through ghastly fear, Ran madding to the downs, with loose dishevelled hair. The sylvans that about the neighbouring woods did dwell, Both in the tufty frith and in the mossy fell, Forsook their gloomy bowers, and wandered far abroad, Expelled their quiet seats, and place of their abode, When labouring carts they saw to hold their daily trade, Where they in summer wont to sport them in the shade. Could we, say they, suppose, that any would us cherish, Which suffer (every day) the holiest things to perish? Or to our daily want to minister supply? These iron times breed none, that mind posterity. Tis but in vain to tell, what we before have been, Or changes of the world, that we in time have seen; When, not devising how to spend our wealth with waste, We to the savage swine, let fall our larding mast. But now, alas, our selves we have not to sustain, Nor can our tops suffice to shield our roots from rain. Jove’s oak, the warlike ash, veined elm, the softer beech, Short hazel, maple plain, light asp, the bending wych, Tough holly, and smooth birch, must altogether burn: What should the builder serve, supplies the forger’s turn; When under public good, base private gain takes hold, And we poor woeful woods, to ruin lastly sold. |

A Forest, containing most part of Kent, Sussex, and Surrey. |